As a musician, you already know how emotionally evocative a great chord progression can be. But part of the beauty of music is creating new and exciting soundscapes and textures. By understanding the basic music theory behind chord inversions, you’ll be able to make the chords you already know more expressive and nuanced.

Chord Inversions for Piano: A Primer

If you don’t have a whole lot of background in music theory, the concept of the chord inversion may be unfamiliar. Here’s what you need to know to start using inversions in your music.

What’s A Chord Inversion?

On the piano, if you play three or more notes at the same time, you’re playing a chord. And just like many chords on guitar, most piano chords are triads. That means they’re made of three notes. This video (above right) offers some useful background on triads.

If you want to add a slightly different feel to the same chord progression or piece of music, you can use what’s called a chord inversion. Most commonly-learned chords are root position triads, which means that the lowest note in each chord is the root note.

A chord inversion just changes which note of the chord is the lowest note (or the bass note). Effectively, when you use inversions, you’re able to play one chord in different ways. The concept of inversions isn’t unique to piano; chord inversions are a great way to add some variety to your music if you play guitar, too!

Why Use Inversions?

Even if you’re technically playing the same major triad, a chord inversion can change the character of a chord. But there are a few other advantages to using inversions in your music.

Inversions are a great tool to use when you want to change the sound or feel of a specific chord progression or song. Certain inversions may sound dreamy or light, while others can sound somber or darker. This video lets you hear the difference between several inversions of the C major chord.

Inversions also can be useful if you want to smooth out a piece of music. Sometimes, having a large jump between the lowest notes of chords in a progression can be jarring. If you use inversions so the frequencies of the bass notes of each chord are closer together, the resulting piece of music will sound more connected and melodic.

Another benefit of using inversions is that it can sometimes make chord changes easier. By strategically including a chord inversion or two in a progression, you can switch chords more quickly and easily!

Start With A Root Position Triad

Now, we’ll get into the details of how an inversion works. The first chord type we’ll look at is a major triad — the C major chord.

In a C major triad, you have the notes C E G. Since there are three notes, this chord will have three inversions (if you count the root position triad). In each inversion, a different note becomes the chord’s lowest note.

Before you understand the chord inversion concept, you need to have at least a basic grasp of scale degrees and how they construct chords. The scale degrees you need to make a major triad are a root note, a major third, and a perfect fifth.

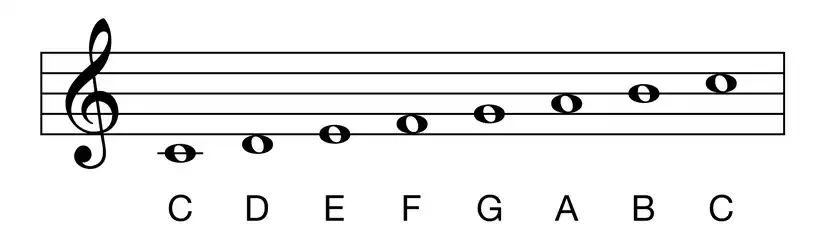

We won’t get too deep into the theory behind intervals (although this video gives you a crash course). But as a brief recap, here’s the C major scale:

The root note of a C major chord is the first note of the C major scale, so C is our root. The major third is the third note in the scale, so the third is E. And the fifth is the fifth note in the scale, or G. That gives us C E G, or the three notes in the C chord. So if you were going to do two inversions of this chord, one would have E as the bass note and the other would have G as the bass note.

Inversions aren’t limited to major chords. You probably recall that the minor version of a given chord just has a flattened (minor) third, so a C minor triad contains the notes C Eb G. If you were to go through the inversions of the C minor chord, one would have Eb as the bass note and another would have G as the bass note.

Major Chord Inversions: 1st Inversion Triad

In the first chord inversion, you take the root note of a triad and raise it by an octave. Let’s stay with the C major chord as our example. Since a regular C major chord has C as the bass note, it’s what’s called a root position triad.

For this inversion, the parent chord has the notes C E G, where C is the lowest note, E is the middle note, and G is the highest note. Since we’re raising C by an octave, C is now the highest note. So the 1st inversion of C major is E G C. More broadly speaking, in any first inversion of a major triad, the third is the lowest note. If you want to see (and hear) the difference between this inversion and others, check out this video.

To really understand inversions, you need to know the intervals between each note. Like we mentioned above, the intervals between the three notes of a root position triad are a major third and a perfect fifth. Since the note order changes in an inversion, so do the intervals.

In the case of the 1st inversion, E is our bass note, with G as the middle note. The distance between these notes (in scale degrees) is a minor third. The distance between G and C (in scale degrees) is a perfect fourth.

That means that the interval structure of a major triad’s 1st inversion is a minor third followed by a perfect fourth.

Major Chord Inversions: 2nd Inversion Triad

The second inversion of a chord means that the third (instead of the root note) is moved up an octave. Our example root position triad is still C major (C E G).

However, to get the 2nd inversion, you don’t need to start with the root position chord; you can start with the 1st inversion. Remember that our 1st inversion is E G C. So we take the third and move it up an octave. That gives us G C E.

So in this inversion, our bass note would be G. A short, easier way to remember the 2nd inversion is that the fifth of the original triad is the lowest note.

And not surprisingly, the second inversion has a different interval structure than the first inversion. The distance between G and C is a perfect fourth, while the distance between C and E is a major third. That means that the interval structure for a 2nd inversion (of a major triad) would be a perfect fourth and then a major third.

If you can remember and use the same three positions of the inversions, it will be easy to add some variety to the music you play. But don’t stress if you can’t remember every bit of theory! Knowing the theory behind a concept can be helpful. But in most cases, being able to apply the key concepts to your music is most important. If you’d like some help learning chord inversions, check out this helpful video.

How Do You Notate Chord Inversions?

You probably already know the chord symbols for major and minor chords. If you don’t, major chords are just symbolized by a letter. So the C major chord is just written as “C.” Minor chords have the chord letter followed by the lower case letter “m,” so C minor is written as “Cm.”

So how do you indicate whether you play the first inversion or second inversion? The chord symbol for an inversion often comes as what’s called a “slash chord.” Though the name sounds exciting, a slash chord is just a chord written as a slash between two letters.

For example, G/D is a common slash chord. It’s said out loud as “G over D.” That means it is a G triad with D as the lowest note. In a G major triad, the root note is G, the major third is B, and the fifth is D. So since the fifth of the original triad is the lowest note, G/D is the second inversion of G major.

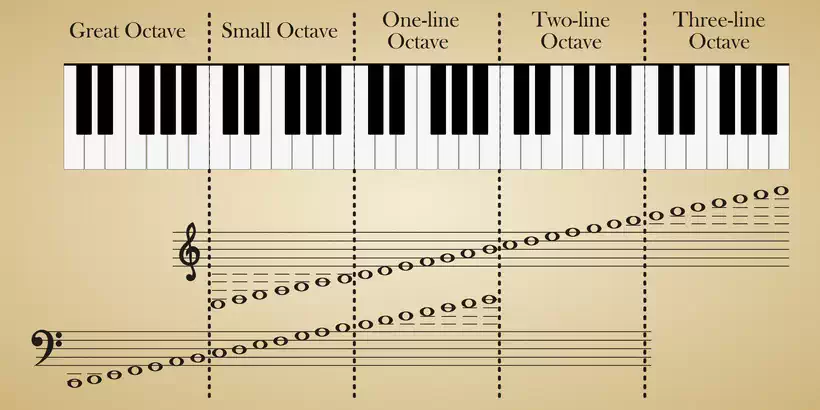

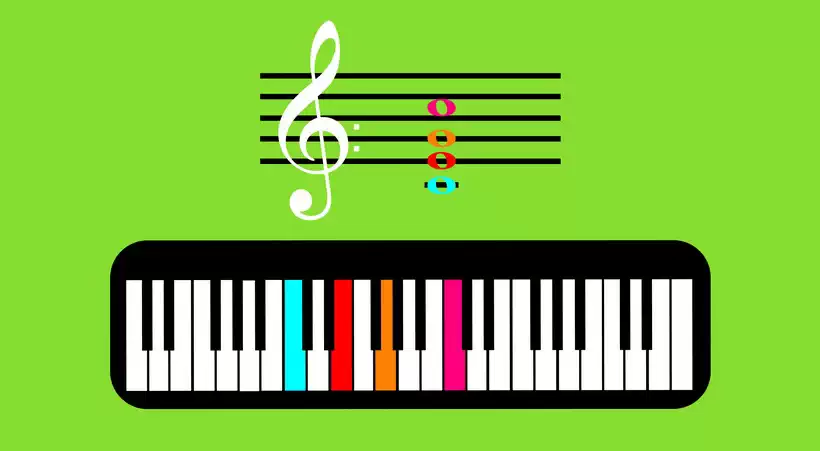

If you can read sheet music, you may not need to remember how to read slash chords. Since a chord inversion changes which note has the lowest pitch, this will be reflected in the sheet music itself. If you don’t yet know how to read sheet music, a chord is shown as a “stack” of notes:

Having the notes in a “stack” indicates that they should be played at the same time as shown in the illustration. If you’re new to reading piano chords on sheet music, check out this video intro aimed at beginners.

Sometimes, you’ll see what is called “figured bass” notation. Figured bass is sometimes part of sheet music. It involves using small numbers next to chord names. The combination of small numbers will indicate what inversion needs to be played.

To the uninitiated, reading figured bass can sometimes seem strange or illogical. But this helpful blog post can help you make sense of it!

What About Other Types of Chords?

We’ve now looked at major triad inversions. But as you likely know, a piano chord is usually made up of three or more notes. But what about extended chords (chords with four or more notes)?

Major seventh chords (not to be confused with dominant seventh chords) are a common example. These chords are made up of both a major triad and a major seventh. The scale degree configuration of a major seventh chord is root note – major third – perfect fifth – major seventh, or 1 – 3 – 5 – 7 for short.

If we again look at the C major scale, the seventh note on the scale is B. So to create a Cmaj7 chord, we combine the C major triad with the major seventh to get C E G B. The C is the root note, so this four note chord is in the root position.

The first inversion of Cmaj7 involves moving the root up an octave (just like the 1st inversion of a triad). So the first inversion is spelled as E G B C. The interval structure is minor third/major third/minor second.

The second inversion will move the third up an octave to give you G C B E. For this one, the interval structure is major third/minor second/major third.

And since there are four notes in Cmaj7, there is a third inversion. For this one, you move the fifth up an octave to give you G B C E. Its interval structure is minor second/major third/minor third. If you want to see all three inversions, this useful video will introduce them to you.

Remembering all three inversions (or more!) for extended chords can be a bit of a challenge. But if you start adding them to your repertoire, you can help both your sound and your expertise evolve.

Want to Learn More?

Though some musicians find music theory boring, you can likely see how knowing at least some music theory can make an impressive difference in your playing. Online piano courses are a great way to incorporate helpful theory concepts into your learning — especially if you’re self-taught.

The right course will break down the most important music theory concepts and teach you to apply them. There’s an online piano course for any level of player; whether you’re just starting out or want to take your expertise to the next level, online lessons can help!

Final Thoughts

Now that you know a little more about how chord inversions work, we hope that you’ll be able to confidently integrate them into your own music. If you’ve worked with inversions before, do you have any tips for those just starting out? And if you’ve found this list useful, please don’t forget to like and share!