Modulation music theory allows you to shift between the music keys to spice up your music and create variety while ensuring musical unity.

In this article, we will cover the relationship between the keys, requirements for modulation, and different types of modulation with their essential concepts and examples.

Read the complete article to learn about all the types of modulations in music!

Definition of Modulation

In music parlance, changing from one tonality or tonal center to another within a piece of music is defined as modulation. Too little variety or too little unity are both not good for music. One bores the listeners, while the other confuses them.

Composers always strive to conjure up brain-friendly variety without impacting musical unity. The 24-key system luckily provides enough harmonic and melodic choices to them in the creation of interesting and compelling pieces while maintaining cohesivity. Simply put, changing from one key to another within a piece of music, often used to help establish form, is defined as modulation. The form is the structure of a composition or performance.

Some call the two keys a parallel universe of notes.

A brief modulation for a few chords, usually 2 to 3, outside the key is known as tonicization. This does not establish a new tonal center. While modulation requires more chords and a clear cadence to be established.

Key Relationships in Modulation

First, we classify the keys into various categories to help us understand the modulation process.

Modulating to Enharmonically Equivalent Key

The tonic notes of the “Enharmonically equivalent” keys are enharmonic equivalents of each other. For example, F# and Gb.

This differs from enharmonic modulation, which will be discussed in later sections.

Parallel Modulation

Parallel modulation occurs to a mode or scale with the same root note. As the tonic is the same, the transition appears very smooth to the listener. For example, C Major, C Minor, C Dorian, and C Lydian are all parallel modes.

Transition to the enharmonically equivalent and parallel keys is not considered modulation. For parallel keys, it is just a change in mode, and the chords used from the other modes are often referred to as borrowed chords or mode mixtures.

Modulating to a Relative Key

As you know, the relative keys share the same notes and the key signature. For example, the C Major and A minor keys are relative to each other and are called relative major and relative minors to each other. This reduces the 24 major and minor keys to 12 relative pairs of keys. Modulation between the relative pairs is known as the modulation to a relative key.

Relative keys also form part of another classification, the closely related keys, which you will be seeing next.

Modulating to a Closely Related Key

This is the modulation within the keys defined as closely related to each other. For each key, you can have five closely related keys. Any two keys are said to be closely related if there is a difference of a maximum of one accidental in their key signatures.

If you select your current key on the circle of fifths. The two keys next to it (its neighbors) – one in a clockwise and the other in an anticlockwise direction are its closely related keys in the same sonority or quality. Next, if you take the relative keys of these three keys, you have the complete set of five closely related keys.

Consider the ‘A’ major key on the circle of fifths. It has three sharps in its key signature. D and E major keys are its neighbors on the circle with two and four sharps, respectively. They have a difference of one sharp in their key signatures from A major. The relative keys of A, D, and E are F#m, Bm, and C#m. Hence, the closely related keys of A major are D Major, E Major, F# minor, B minor, and C# minor.

The modulation appears less jarring, unsettling, and dramatic in closely related keys with a smoother transition.

Modulating to a Distantly Related Key

Modulation to any key other than the closely related keys is a modulation to distantly related keys. C and D Major keys with a difference of two sharps in their key signatures are examples of distant keys.

Requirements for the Modulation

We will be discussing the requirements of each type of modulation in detail in the individual section. Let us briefly summarize some important terms and requirements that form the core concepts for modulation in music.

- Harmonic – The presence of quasi-tonic, modulating dominant and pivot chords. The quasi-tonic is the tonic of the new key. The modulating dominant is the dominant chord of the quasi-tonic. A pivot chord is usually a chord common to the new and the old key. It is also a predominant chord in the destination key.

- Melodic – A recognizable segment of the new scale or its leading tone placed strategically.

- Metric and Rhythm – The new tonic and its modulating dominants must be on metrically accented beats, along with the prominent pivot chord.

Types of Modulation

Let us now begin our review of different types of modulations, starting with the most commonly used one – the common chord modulation.

Common Chord Modulation

To explore the possibilities of a common chord modulation between the two keys, you may carry out the following steps.

- Write the lead sheet symbols for all the diatonic chords in the current key. Let us consider Bb Major as the original key. Its chords are [Bb, C-, D-, Eb, F, G-, Ao]. It has two flats in the key signature.

- Next, note down the lead sheet symbols for the new key, let’s say C minor. The chords are [C-, Do, Eb, F-, G, Ab, Bbo]. It has three flats. So both the keys are closely related.

- The common chords that occur in both keys are C- and Eb major.

- The transition of C- is from the ii chord to i, and for Eb, it is from IV to III in the new key.

The pre-dominant chords, ii and IV, are the most common pivot chords.

Analyzing Common Chord Modulation

You can analyze a common chord modulation in any given piece of music using the following steps:

- The most important step is to find the point of modulation. To do so, look out for the first chord that is not in the original key, or it is a tonic6/4 for the second key.

- Once you have identified a non-diatonic chord, you must satisfy yourself that it is not just a tonicization. The modulation will have a cadence in the new key after the key change.

- To do so, go back by one chord and check if there is a common chord between the two keys, also known as a pivot chord.

Using Pivot Chord

Consider the following example,

D – A7/G – D/F# – C#o/E – D – D/A – A – D – G#/B – A/C# – Bm/D – E7 – A.

If you start putting the Roman numerals into the given chord progression in the key of D major, you get the following.

I – V4/2 – I6 – viio6 – I – I6/4 – V – I, till the D before the chord G#/B. Now G# is not in the key of D. The total chord progression ends with E7 – A. Please note that E7 is the dominant 7th chord of A. There is a likelihood of a key change to A at G# chord

As stated in the steps above, you need to go back by one chord from G#, i.e., the D chord, and check if it is in the key of A. It is the IV chord in the key of A. If we analyze now considering the new key A, we get the progression from the D and G# chords as

IV – viio6 – I6 – ii6 – V7 – I.

This is a valid chord progression in A, resulting ultimately in cadence. Hence the pivot chord modulation has taken place at the common chord D, followed by a cadence with the modulating dominant and the new tonic chord, or the quasi-tonic as seen earlier.

Let us analyze the chords without considering the modulation at G#. The Roman numeral analysis for the chords in the old key is

viio6/V – V6 – vi6 – V7/V – V.

As you can see, you are going from V6 to vi6 in the old key, which is odd as we always go from the V to vi in the root position for deceptive cadence and never in the first inversions.

Hence the total progression in Roman numerals is

I – V4/2 – I6 – viio6 – I – I6/4 – V – I(IV) – vii06 – I6 – ii6 – V7 – I.

Here the progression in the old key is shown in blue, the common chord in green, and the progression after the key change in orange.

The steps for analyzing the other types of modulations discussed below remain the same and are summarized here as under.

- Find out the point of modulation, whereby you find a chord that is directly related to the 2nd key only.

- Go back by one chord and analyze it as described for the different types of modulations below.

Altered Common Chord Modulation

In the altered common chord modulation, the pivot chord is altered from a chord that belongs to either the old or new key or both. They can be the secondary chords V7 and viio7 chords in the first, second, or both keys. Consider the following chord progression in the key of C as an example.

G7 – C – Dm – D7 – G

The D7 chord with notes [D, F#, A, C] is not in the key of C. In addition, D7 is the V7 chord of G and Dm is the ii chord of C. So the point of change is D7, which is a secondary dominant of G. Hence, the progression can be written in the roman numerals as

V7 – I – ii – [V7/V (V)] – I

Here [V7/V (V)] denotes that the chord’s designation has changed from V7/V in C to V in G.

Just a word of caution that secondary dominants are used for tonicization also, where you quickly return back to the previous key. You need to be sure before treating the change as a modulation. In the example above, a cadence (V – I) has happened after the change in the new key, so it is a modulation.

Chromatic Modulation

A chromatic modulation is characterized by a chromatic chord, which has chromatic inflections in one or more notes. A chromatic inflection means that the letter name remains the same, but the accidental has changed. This happens in keys with distant relations.

For example, consider the key of G major and the progression

IV – V/ii – ii, which translates to C – E – Am.

Observe the notes of these chords with

- The C major chord [C E G],

- V/ii, or the E chord [E G# B], and

- The Am [A C E].

The notes G – G# – A in the three chords transition the chromaticism and can be written in any one voice out of the four for voice-leading purposes.

The progression can now transition to a new key, A minor, from the Am chord through chromatic alteration introduced in the secondary dominant V/ii chord from note G to G#.

Chromatic Mediants

In continuation of the chromatic modulations discussed above, let us examine the chromatic mediants, which are at thirds from each other and have a mediant relationship in a scale. For example, G and Bm chords in the key of G.

These chords have two notes with the same letters between them. For example, G major chord [G B D] and the Bm chord [B D F#] have B and D as common letters. This is called the mediant relationship.

As you know, the chord formed with a note at degree 3 as root is said to have a mediant function. It has notes [3 5 7] in a major scale. The tonic chord has [1 3 5]. So two notes, 3 and 5, are always common in the two.

If you alter one of these common notes, you get a chromatic mediant relationship, and if you alter both notes, you have a double chromatic mediant relationship. Examples of these two types are

- Chromatic mediant relationship: G major [G B D] and B Major [B D# F#] chords. Here, D in the G major is altered to D#. The only same pitch is B.

- Double chromatic mediant relationship: G major [G B D] and E minor [E Gb and Bb] chords. G and B are common letters but altered by the addition of flats.

We can use them in creating modulations in the same way as the chromatically altered chords.

Sequential Modulation

A sequential modulation happens with or without a common chord. It can happen by repeating the same pattern melodically and harmonically. A passage in 1st key may end in a cadence and start again in a new key after transposition. A sequential modulation is sometimes termed the Rosalia.

For example, consider the following sequence in G.

I – V7 – vi – IVM7 – V6/V – I6/4 – V

If this is followed by,

i – V7 – VI – V6/V – i6/4 – V

in A minor key. The modulation happens at i, i.e., the Am chord, due to the same sequence getting repeated. The modulation is considered sequential even though Am chord occurs in both G and A. It is common to have a sequential modulation by

- Going up a step, as in the above example.

- Going down a step, or

- Going as per the circle of fifths.

Common Tone Modulation

This modulation type uses a common tone, also known as the sustained or repeated pitch, between the two keys to modulate. Common tone modulations are usually carried out to the diatonic or chromatic thirds.

The transition by a common chord is smooth, and you may not even come to know if the modulation has happened if you are not listening carefully. A common tone modulation is pronounced and dramatic. It is like prewarning your listener that something is going to happen. Beethoven made extensive use of this form of modulation.

We had discussed above that the chromatic mediants have differences in one or two tones and can also be used for this purpose.

An example is,

F#m: V – i6 – i – V – i6 – i – V – (~5/~3) – I – V7

The progression starts with the F#m key. The (~5/~3) denotes the common tone, which is at scale degree 5 in F#, i.e., the C# note. The same tone, C#, is at the scale degree 3 in the key of A major. Hence the modulation occurs at this common tone to A major.

See the notes of the chords F#m [F#, A, C#] and A major [A C# E]. They are in a mediant relationship, and in the progression above, we have used C# out of them as a common tone.

Monophonic Modulation

This happens in the cases of monophonic instruments playing one note at a time, like the violin. These instruments do not play chords, which are implied.

If you change to new pitches which are not diatonic, it implies a modulation. For example, a change from Bb to B followed by E may imply a change from F major to E minor scale.

Chain Modulation

You can achieve the modulation to the distant keys in steps by going through the closely related keys. To do this, you can use the following two methods.

- Use the circle of 5ths and reach E from C by going through G, D, and A. This can be done by using the dominant seventh chords in progressions like C – C7 – G – G7 – D – D7 – A – A7 – E.

- You can use the parallel and relative major or relative minor keys. For example, to reach C minor (with three flats) to A minor with no flats, you can transition through Cm – C – Am keys. You can even use a mixture of both of these methods.

Direct Modulation or Phrase Modulation

Direct modulation is also known by other names like abrupt modulation, static modulation, or phrase modulation. The direct modulations do not make any attempt to be smooth and may happen with or without the use of a common chord.

The first phrase ends with a cadence in the previous key, and the second one starts in the new key without any transition or linking between the two. We can use the example of sequential modulation, where we do not maintain the harmonic or the melodic sequence, and after the first phrase in G, the second phrase can be

i – III – iv – i6/4 – V – i

in A Major. The above was an example of modulation happening at the completion of the phrase. Its use within the phrase is the last resort and produces a very dramatic effect.

Enharmonic Modulation

It is a form of the common pivot chord modulations, where a chord is enharmonically interpreted to be a common chord. These modulations use either a dominant seventh chord or the fully diminished chord in the role of a pivot.

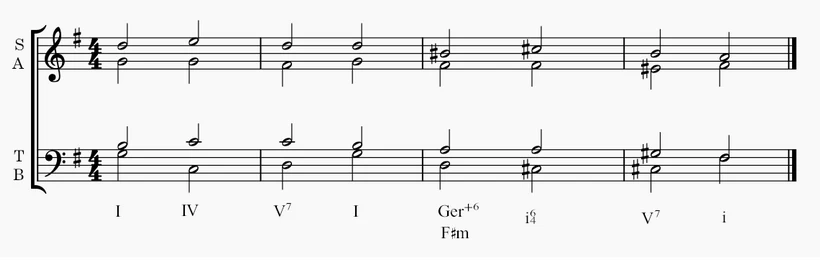

Modulation Using Dominant 7th and Augmented 6th Chords.

You might have gone through our separate articles on the dominant seventh (Dom7) and the augmented 6th (Aug6) chords. A Ger+6 chord can be shown to be enharmonically equivalent to the Dom7 chord. While they serve different functions in harmony but are enharmonically equivalent.

This method is used for modulation to a key, which is usually half step lower.

Consider the D7 Chord in the key of G with notes [D F# A C]. The Ger+6 chord in a key which is a half step lower than G, the f#m is [b6 – 1 – b3 – #4], i.e., [D F# A B#]. You may note that the first three notes in the two chords are the same, and the 4th notes are enharmonically equivalent notes B# and C.

This enharmonic modulation is shown in the diagram below.

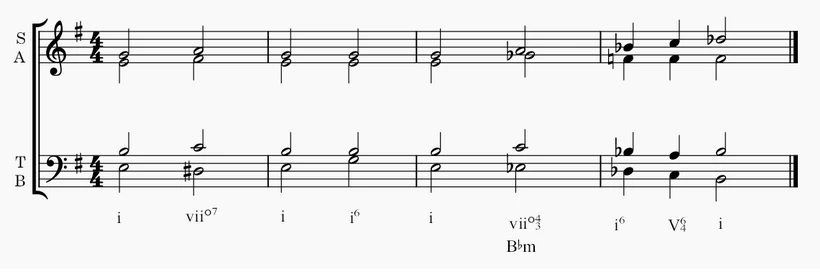

Modulation Using Diminished 7th Chords

The fully diminished chords can be used to modulate to the keys, which are a minor third or tritone apart. This is because there are three more enharmonic equivalents for every such chord. Consider the D minor key, whose viio7 chord is C# with notes [C# E G Bb]. Let us take the three version of this chord and their enharmonic equivalents.

- viio6/5 = [E G Bb Db] = Eo7 chord, which is the viio7 chord in the key of Fm.

- viio4/3 = [G Bb Db Fb] = Go7 chord, which is the viio7 chord in the key of Abm.

- viio4/2 = [A# C# E G] = A#o7 chord, which is the viio7 chord in the key of Bm.

Hence, we can use these chords to modulate from Dm to Fm, Abm, or Bm, as these are just inversion and enharmonic equivalents of the original chord.

The below diagrams on sheet music show the key changes from Em to Bbm at a distance of a tritone.

Conclusion

We hope that all the modulations explained above are now clear to you and you can try to incorporate some of them into your music. If you require to have any additional information or need clarifications, please comment in the section below.