Harmony in Music is an essential part of creating beautiful-sounding music.

Harmony can be used to create chords and progressions. It’s one of the most important aspects of music composition in Western Music.

If you’re interested in learning more about harmony and how to use it in your own music, then keep reading. You’ll find everything you need to get started right here.

What Is Harmony?

Melody, rhythm, and harmony are the three building blocks of music, sometimes also referred to as the three types of properties or dimensions of music. Each of these further has a finite number of elements defining them, such as chords, scales, modes, arpeggios, rhythmic figures, melodic patterns, etc. Each of these elements can be combined in different ways giving you infinite permutations to try out.

Metaphorically, they can be compared to the height, width, and depth (or three dimensions) of the music.

- Melody defines the height with the pitch, duration, and intensity of the sound.

- Rhythm defines the width or time with the elements like beats, duration, and beats per minute.

- Harmony defines the depth of the music. The combination of the musical notes played simultaneously as a chord results in a depth-like quality. Harmony may be thought of as a dynamic landscape for the melody to travel.

Harmony is defined as the science dealing with the structure of the chords, the relation among various chords, and their progressions. So, in a nutshell, it covers three main aspects:

- The chord structure with respect to the number of notes, their intervals, the principles of chord formation, etc.

- The relation between the chords is usually defined by their scale degrees.

- The chord progressions.

The synonyms of harmony are congruence, consonance, symmetry, and symphony.

Different Types of Harmony in Music

The different types of harmony in music are:

Diatonic Harmony or the Tonal Harmony

In the diatonic harmony, all the notes and chords are from the same master scale related to a key or tonic center. If you play in E major scale, all the notes in the melody and the chords will be derived only from the seven notes in the key of the E major.

Most of the modern music in the world falls in the category of Tonal music, which means it has a tonal harmony. All the notes, chords, and scales in a piece of tonal music derive their harmonic function from the tonal center and either move away from or move toward it.

Non-Diatonic Harmony

Though used in all genres of music, it is more prevalent in jazz music. The chords used may contain notes which are not part of the original scale. For example, if you are playing in the key of C major and use the D7 chord (V/V or secondary dominant chord) with notes D, F#, A, and C, it forms a non-diatonic harmony.

Modal Harmony

In modal music, a scale or a mode acts as a center of gravity instead of a single tonic note. While there is still the key for the scale, it does not yield that much control over the harmony. In such an arrangement, all notes equally define the harmonic function. Instead of representing the key as A minor, it is written as “A Dorian,” which indicates that though the scale begins with the A note, it is not the tonal center.

Modal harmony was used in old periods in Europe and has been in continuous use in Asia and Africa. It was revitalized again in the 20th century, and the invention of modal jazz in the 1950s brought it more into prominence.

Polytonal Harmony

It can be either tonal or modal. More than one tonal center is established at a time. More than one note can be the tonal center, or more than one mode can be used together to establish modal harmony. The harmony is very dissonant and complex.

Atonal Harmony

This is an extreme case of polytonality where all twelve notes are treated like tonal centers. The concept allocates more importance to the notes and their interaction with each other rather than being concerned by their interaction with some tonic note. It was developed by Austrian composer Arnold Schoenberg based on his serial system.

Concepts of Consonance and Dissonance in Harmony.

Before we move deep into the three main aspects of harmony, structure, relations, and progressions, stated above, let us introduce a few helpful concepts from music theory.

While a melody can stand on its own, harmony without a tune does not appear as a piece of music to your brain. We discussed consonant and dissonant sounds, dissonant and consonant intervals, consonant and dissonant chords, and other aspects associated with dissonance in music in our detailed article on the topic.

While we will not repeat the concepts covered there, let us summarize the main aspects of the article referred to in the last paragraph to clearly understand the underlying principle of harmony in music.

- The consonant chords are formed by organizing the scale degrees related to the overtones of the harmonic series, where scale degree is the designation of each note in the diatonic scale. The organizing principle is not related to the overtones themselves.

- The ratio of these overtones has simple ratios, which are the same as those between the notes of a major or minor scale.

- Most of the strong overtones are related to scale degrees 1, 3, and 5.

- When you play these notes as a triad, the overtones related to the three notes reinforce each other. Hence any major triad is stable and consonant.

- As harmony involves chords, consonant harmonies require only consonant chords.

- Even if one of the internal and outer intervals is dissonant, the entire chord becomes a dissonant chord.

- Any minor or major chord is consonant, while all diminished, augmented, 7th, extended, and altered chords are dissonant chords, as they have one or more dissonant intervals.

- Basic concepts related to tonal music and its counterpart, atonal music, were introduced.

How Is Harmony Represented in Music?

As stated above, harmony is the complex and coherent unified result of playing two or more notes together. Multiple different-pitched notes are played together to form a chord. Chords are played in succession to form a chord progression.

You cannot figure out the individual notes in a chord, even while fingerpicking the chord changes or playing arpeggios on the keyboard. That’s what makes them different from any melody. The distribution of chord successions in time is noted by the brain but not the individual notes.

We have similar terms as the melody to define harmony, though not as frequently used. Like scale degrees, melodic intervals, and scales in melody, the harmony is characterized and organized by the harmonic degree, harmonic intervals, and the harmonic scale. Let us familiarize you with them. Note the correspondence with the melodic terms to easily remember them.

Harmonic Degrees

Chords are known as the harmonic degrees and are denoted by the Roman numerals I, II, III, and so on. This is just like the relation between the notes and the scale degrees and their identification by Arabic numbers 1, 2, 3, and so on, based on the scale position.

The roman numerals denote a complete chord named after the root note. The root notes are related to the scale degrees. This defines the relationship between the melody and harmony. The seven harmonic degrees are the triads whose roots are the seven scale degrees of the diatonic scale. This is also the basis for the Nashville Number system of chords.

| Chord / Notes | Chord I | Chord II | Chord III | Chord IV | Chord V | Chord VI | Chord VII |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Root of Triad | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Third of the Traid | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 2 |

| Fifth OF the Triad | 5 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

Starting with any root, select the 1st, 3rd, and 5th notes of the diatonic scale. You will see that these notes will always form a triad. This is because the interval between the alternate notes of these scales is always a major or a minor third. As you can see, the harmonization of relative scales results in 3 major, 3 minor, and 1 diminished triad.

The three major chords cover all seven notes of the parent major or minor scale. The same holds true for the three minor chords.

Harmonic Intervals

The succession of chords or a chord progression proceeds by harmonic intervals, much the same way as the notes in tune follow the melodic intervals. In simpler terms, the harmonic interval means a chord change. A succession of melodic intervals is represented as,

1 – 5 – 4 – 2 – 1, with each number representing the scale degree.

In the same way, the succession of harmonic intervals is denoted as,

I – VIm – IIm – V7 – I,

where each roman numeral denotes a harmonic degree, each dash a change, m represents minor chords, and V7 represents the 7th dominant chords. In this representation, there are five chords undergoing four changes.

In a chord change, the overall sound changes, which has nothing to do with the rise or fall in the pitches of the individual notes. The overall sound change manifests itself as a change in color. The individual pitch changes in most chord successions are actually very small and usually limited to a whole tone.

The harmonic interval is represented as an interval between the roots of the chords. But you must clearly understand that it is the whole chord that changes, and just the root movement has no meaning by itself.

The common harmonic intervals are:

- 5th progressions, up and down.

- 3rd progressions, up and down

- 2nd progressions, up and down.

- Chromatic progressions.

Understanding the Nomenclature for Naming the Harmonic Intervals

You might be a bit confused about the nomenclature – 5th progressions, up and down, used in the list above. The following may clarify the concepts.

- In harmony, the complementary intervals have the same names.

- In C – G – C progression, the C – G and G – C are complementary intervals. In melody, they are known as 5ths and 4ths. In harmony, they are known as the 5ths only. The same logic applies to the 3rds & 6ths and the 2nds & 7ths.

- Hence there are only three types of progressions from serial 1 to 3 on the list.

- Up and down means counting forward and reverse. Write down the two roots such that they denote the 5th melodic interval, like C – G (and not G – C). C – G will then denote the 5th progression up as we move in the forward direction of the alphabet (C, D, E, F, and G). G – C is its complementary interval, and the note names are in reverse alphabetical order (G, F, E, D, and C). Hence it is named the 5th progression down. Up and down is not related to pitch in any way. For the A and D intervals, the melodic 5th is D – A. Hence D – A is the 5th up (D, E, F, G, and A), and A – D is the 5th down (A, G, F, E, D).

- The same naming logic applies to 3rd and 2nds progressions.

A fifth-up progression has different harmonic characteristics than the 5th down. A chromatic progression involves a chord whose root is not in the key of the concerning scale.

Harmonic Scale

The harmonic scale is formed by placing the seven chords of a diatonic scale in a specific order. This is similar in principle to the diatonic order or structure of the seven notes of the diatonic scale.

There are 24 major and minor scales in Western music, starting with the 12 notes forming the chromatic scale. You are aware that the relative scales carry the same notes. There are 12 harmonic scales, each with a pair of relative major and minor keys.

The harmonic scale is shown below. You may note the following important characteristics of the scale:

- The scale is made for a particular major and its relative minor key.

- It shows the arrangement of chords in a circular pattern, with Vths being the harmonic neighbor of every harmonic degree. This means every chord in the clockwise direction is the 5th progression down. It takes the shape of a circle as there is only one harmonic center, as against the root and octave being two tonal centers in melodic scales.

- The underlying principle is that the V – I is the most natural and the strongest progression in harmony. It has both unrest and direction. The scale degrees 7 and 2 seek resolution to the tonic. The V chord has both these notes. In addition, it has a simple frequency ratio of 3/2 with the root and has a similar major key signature with the difference of only one note with the tonic. Hence, the V chord provides the perfect cadence.

- Only the tonic chord in the root position has no tension or direction. All chords, other than the harmonic degree V and I, have only tension but no direction.

- You can move only in a clockwise direction on the circle. This direction resolves tension and unrest. Tension & unrest increase in the anticlockwise direction.

- The generic harmonic degrees are shown on the inside.

- The harmonic degrees with respect to the selected keys are shown on the outside. The scale has three major chords on one side and three minor chords on the other. The transition in the clockwise direction happens through the diminished chord.

- The harmonic scale maps the chord progressions of any song in what is known as a Chase chart. The numbered arrays show the actual succession of chords. The Chase pattern demonstrates the strength, weakness, and appeal of any progression.

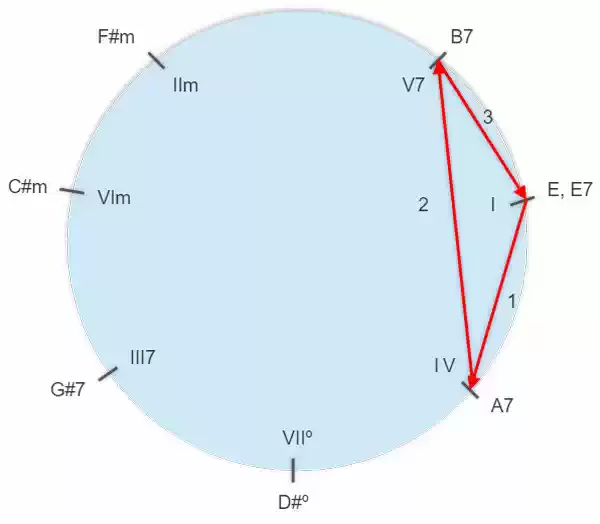

- The below diagram is for the harmonic scale in the key of E major for the song “Heartbreak Hotel.” The seven actual chords used or in the key are shown outside. The generic chords are shown inside, which do not change with the key. The red line shows the I – IV – V, eight-bar blues progression, with each red line having a number 1, 2, 3, etc., showing how the progression proceeds.

How Is Harmony Used in Classical Music?

Consonance and dissonance are both important for music, as the first provides balance and stability in music apart from establishing tonality. However, only consonant intervals and harmonies are very boring. You require movement, instability, tension, a compelling story, sonic unrest, and drama in music. That’s where the dissonance comes in.

Harmonic Motion

The purpose of the consonant triads, like a major or a minor chord, is similar to the tonic note in a melody. To establish and keep the tonality reinforced. Your brain can note any departure from tonality only after it is established. It may be considered as a reference against which any movement or unrest can be noticed. After establishing the scale degree 1, the movement in music is created by

- Horizontal harmony: Changes in the notes of a melody line away from tonic through a succession of intervals.

- Vertical harmony: Playing chords in succession, thereby introducing dissonance in addition to manipulating the existing tonal tension.

- Changes in the key: Through tonicization or modulation. As you may be aware, modulation is the extended change in a key within the piece of music and is both melodic and harmonic in nature. It establishes a new tonal center. While tonicization is the change in key for a small period, usually too small to establish a new tonal center. No authentic cadence is established to the tonicized key.

How A Chord Progression in a Harmony Works

As stated earlier, most types of chords, other than the main triads, result in dissonant harmonies. Reverting back to a consonant chord like these simple triads restores the consonance.

Hence the chord progressions serve the following purposes in harmony:

- As stated above, they help in defining the tonality of any piece of music.

- Like different notes of a tune other than the tonic, other chords in a progression provide the movement and drive to the music. These chords are dissonant and create restlessness and tension, seeking a resolution.

- They provide depth and color to the music.

Some Important Features of Chords in a Musical Composition

The sound of a chord is not impacted by inversion, as the octave in which any note does not affect the chord. Also, since a chord produces a unified sound, the order in which you play them does not have any material impact.

As you learned earlier, a tonic chord of a major or minor key is a balanced and stable chord without any movement. However, melody always has precedence over harmony. As soon as the notes of the melodic line move away from scale degree 1, even the tonic chords in a major key acquire the dynamic quality of unrest.

If the tune goes through a state of unrest, the accompanying consonant harmony cannot alter the state. Your brain always gives precedence to the tune.

Popular Example of Harmony in Music

What Is an Implied Harmony?

We call it an implied harmony when all the notes in a chord are either not played or are not played simultaneously, but the listener’s brain can still figure out the missing part and the chord as a whole.

Harmony can be implied through arpeggiation, counterpoint, etc. In these scenarios, the note is omitted, but the context will fill in the missing details. Or the different members of the harmony occur at different points in time, but the tying and slurs make them a part of the same harmony.

As you may be aware, the counterpoint refers to the texture in music, where you may have more than one melodic lines that are equal in importance. The individual melodic line is referred to as a counterpoint. There has always been a debate on the precise definition of harmony and whether contrapuntal (successively sounding tones) should be a part of it.

Some examples of implied harmonies are

- Beethoven’s Opus Sonata 57 – The F minor chord is played through arpeggiation.

- Art of Fugue by J. S. Bach – The different notes of the C Minor 7 chord are not played simultaneously, but tying results in the intended chord.

Other common examples are from the 7th chords, as shown below:

- The CM7 major chord {C, E, G, B} can be played simply through E and B notes (a Perfect 5th apart) with C as the bass. You may omit the G note as an implied harmony.

- Similarly, Gm7 minor chord {G, Bb, D, F} is played using Bb and F with G as the bass.

- D7 chord is played with F# and C using D as the bass.

Similarly, all the extended chords are played by leaving out some notes, implying them.

Close vs Open Harmony

Chords with a separation of not more than one octave between their top and bottom notes are said to have a closed structure or a closed position, or close harmony. On the other hand, those with a separation of more than one octave are referred to as the open position chords or are said to be in open harmony.

Tertian, Quartal and Quintal Harmony.

Simple triads like C major triad are built with the interval of thirds stacked over the root note. These chords are said to be in tertian harmony. Building the harmonic structures with the intervals of 4ths (Perfect, diminished, Augmented) is known as quartal harmony; for example, C – F – Bb. Similarly, stacking the intervals of 5ths (Perfect, diminished, Augmented) results in a quintal harmony, like C – G – D.

Monophonic Harmony

This involves producing identical notes together, an important consideration in orchestration. The use of this concept is quite prevalent in pop music. Playing the same notes on different musical instruments simultaneously or singing in unison (known as unison singing or doubling) is known as monophonic harmony.

This is against the counterpoint or polyphonic harmony we spoke about earlier.

Conclusion

We hope that we have been able to provide you with a good introduction to all the salient points about harmony in our article above. While it may be too much information, if you are an absolute beginner, it does provide you with an overview of the things associated with harmony and harmonic relationships. We urge you to provide your views in the comment section below or if you require any clarifications on the above.

What was the type/style of harmonies always used in the late 1930’s, the 1940’s and much of the 1950’s? – usually on the radio or movies. I know there’s as name for it but don’t know which one.