Intervals can be confusing for guitar players. If you don’t understand intervals, you’ll have a hard time making sense of the music you’re trying to learn. Even experienced guitar players can find intervals confusing. There are so many different types and qualities, and it’s hard to keep track of them all.

We’ve created this guide to help you understand guitar intervals clearly and concisely. You’ll learn about the different interval qualities and how they apply to major and minor scales, chords, and even the concept of inverted intervals. After reading this guide, you’ll have a strong foundation in intervals and be able to apply them to your playing.

What is A Guitar interval?

An interval in music is defined as the relationship between two notes with a unique sound. It is a measure of the harmonic distance between them. The first note of the two is called the root note, and the second is the interval.

Each interval is characterized by a unique name and sound. The interval names are derived from their position in diatonic scales.

We introduced you to the concept of notes as a musical alphabet, tones, semitones, steps, half steps, etc., in our article on guitar music theory. This article will build upon the knowledge to clarify all the concepts related to the intervals.

The concept of interval forms the basis of defining any scale, including minor pentatonic, major pentatonic, blues scale, etc.

Melodic and Harmonic Intervals

We can classify all the intervals by the way we play them. Understanding the two ways of playing them will go a long way in developing a better understanding of guitar chords and scales.

Melodic Intervals

Any interval is called a melodic interval if the two notes are played one after the other, with only one note played at a time. The two notes can lie on the same string, on different strings, and can have different distances. The only important consideration is that if you are playing one note at a time, you are using melodic intervals. These are used a lot in soloing or a lead line.

Harmonic Intervals

Two notes in any harmonic interval are played simultaneously, making harmonic intervals the building blocks of any chord. A power chord is also a type of harmonic interval.

You would have understood by now that.,

- Harmonic and Melodic Intervals are the building blocks of chords and scales.

- You use the melodic intervals in Solo guitar playing and harmonic ones in chord progressions.

Guitar Intervals Spelled Out

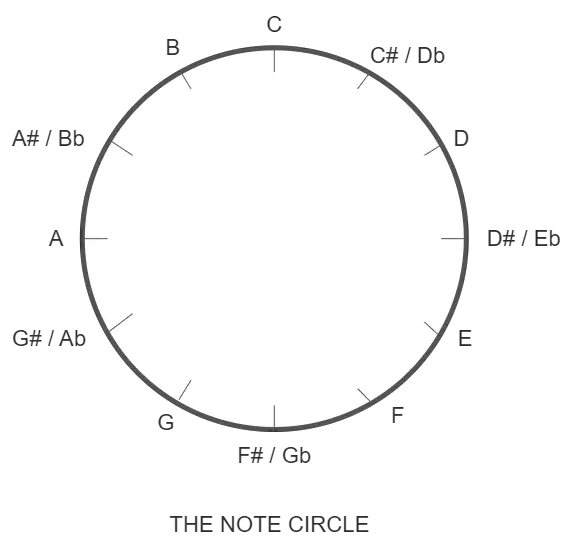

We introduced the concept of the notes circle during the discussion on music theory. If you start on any note, called the starting note, and play any other note, you will play an interval of some type. You can choose any note as the root note and define intervals for all the notes on the circle. Let us choose C as the root note.

Perfect Unison (C to C)

The interval with zero distance is known as “Perfect Unison.” It is when you play the same note twice. You will get a nice and thick sound if you play it as a harmonic interval on a perfectly tuned guitar. However, a slightly out-of-tune guitar will produce a wobbly and unstable sound. Playing unison is a quick way to check your guitar tuning.

Minor Second Interval (C to C#/Db)

C#/Db is a “minor 2nd” or one-half step / one semitone above C and is usually denoted as m2 (small m). The distance between these notes is one fret on a guitar.

Major Second Interval (C to D)

D is a “major 2nd” interval above C. This is one whole tone / two semitones / two half steps above C. It is denoted by M2 (Capital M) and is at a two-frets distance on guitar.

Minor Third (C to D#/Eb)

If you move further on the note scale in the clockwise direction, you will reach the D#/Eb note, which is said to be “minor 3rd” above C. It is denoted by the nomenclature m3 (small m). It is a convention that major intervals are denoted by capital M and minor ones by small m. A minor third represents three half steps or three frets distance from the root.

It is one of the more important intervals on guitar and provides the characteristic dark or sad quality to the minor scale and minor chords. All triads are made by stacking minor and major 3rd intervals over the root note. Chords just made of 3rd intervals stacked over each other are said to be in tertian harmony.

Major Third (C to E)

Note E is “major 3rd” above C, at a distance of four semitones or four frets on the guitar. Being a major interval, it is denoted as M3. The major third is another important interval that provides bright or happy flavor to the major scale and chords.

Perfect Fourth (C to F)

The note F is a “perfect 4th” above C, with a distance of 5 semitones or five frets from the root note, and is denoted as P4. These intervals are said to be perfect because they are the same in any major or minor scale and most of the other diatonic scales. Don’t worry if some of these names or terms don’t make sense to you at this stage. It is more important to understand their usage and the related context.

Augmented Fourth (C to F#/Gb)

F#/Gb is “augmented 4th” above C. It is also known as a diminished 5th interval. The augmented fourth interval is denoted as A4/d5 and lies at a distance of six semitones or frets. We will introduce you to the different interval shapes and qualities in the later sections of the article.

This is a highly dissonant interval and is not commonly used. It is also termed “tritone” and is the only interval that is an inversion of itself. We will cover inversions in the next section. As you might have guessed, the tritone is an interval of three whole tones. It sometimes functions as a sharp 4th, and at other times it is a flat 5th.

This is the outer interval in any diminished triad. The outer interval, as you may know, is the interval between the two extreme notes of any chord, i.e., the root and the 5th in basic triads and the root and the 7th in the 7th chords.

Perfect Fifth (C to G)

G is a “perfect 5th” or seven semitones/frets above the root note C, denoted as P5. You may be aware that this interval is what constitutes a power chord. It is an interval that features in any major and minor chords.

This interval also forms the basis of the circle of fifths, which is a diagram connecting all the 12 chromatic notes in Western music. The circle provides you the information about the sharps and flats in any given key signature.

Minor Sixth (C to G#/Ab)

G#/Ab note is a “minor 6th” above C, at a distance of eight semitones/frets from the root, and the minor sixth interval gets denoted as m6. It is also known as the augmented 5th interval, which is the outer interval in the augmented triads.

Major Sixth (C to A)

A one-half step above the minor 6th lies the “major 6th” interval, denoted as M6, and nine frets/semitones above the root note C. Like any major interval, the major sixth is bright and happy sounding.

Minor Seventh (C to A#/Bb)

If we continue our clockwise journey on the note circle, we will come across A#/Bb note, a “minor 7th” above C and denoted as m7. As you can figure out by now, it is ten semitones/frets above C. Minor seventh interval is an important ingredient of any dominant 7th chord.

Major Seventh (C to B)

B is a “major 7th” above C, denoted as M7, and lies at a distance of eleven frets/semitones.

Perfect Octave (C to C)

The next interval is 12 frets or one octave higher than the root completing the full note circle.

In all, we encountered four major intervals (2nd, 3rd, 6th, and 7th), four minor intervals (2nd, 3rd, 6th, and 7th), four perfect intervals (unison, 4th, 5th, octave), and one strange interval tritone (Augmented 4th or diminished 5th).

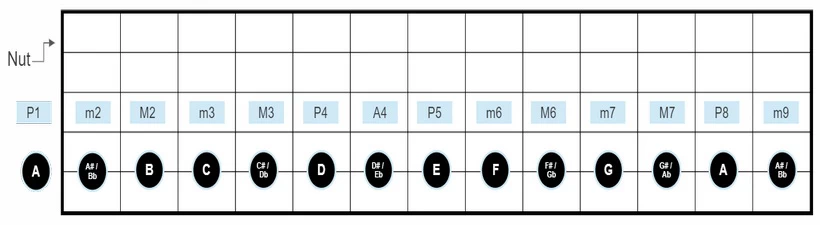

Table of Intervals with root note “A”

The table below lists down all the notes at these intervals, with “A” as the root note and the fret number on the guitar fretboard from the root.

| Perfect Unison | P1 | A | 0 semitone | Zero Fret |

| Minor 2nd | m2 | A#/Bb | One semitone | First Fret |

| Major 2nd | M2 | B | Two semitones | Second Fret |

| Minor 3rd | m3 | C | Three semitones | Third Fret |

| Major 3rd | M3 | C#/Db | Four semitones | Fourth Fret |

| Perfect 4th | P4 | D | Five semitones | Fifth Fret |

| Augmented 4th | A4 | D#/Eb | Six semitones | Sixth Fret |

| Perfect 5th | P5 | E | Seven semitones | Seventh Fret |

| Minor 6th | m6 | F | Eight semitones | Eighth Fret |

| Major 6th | M6 | F#/Gb | Nine semitones | Ninth Fret |

| Minor 7th | m7 | G | Ten semitones | Tenth Fret |

| Major 7th | M7 | G#/Ab | 11 semitones | Eleventh Fret |

| Perfect Octave | P8 | A | 12 semitones | Twelfth Fret |

Notes above the Octave

To distinguish the notes in the current octave from those in the next higher octave, we define intervals by adding 7 (seven) to the name in the first octave. A major second becomes a major ninth, and a minor second becomes a minor ninth. The concept is useful when we deal with extended chords.

Inverted Intervals

So far, we have moved clockwise in the note circle, which means going from a lower pitch to a higher pitch. What if we go from a higher pitch to a lower pitch? Will the intervals be the same as those defined above? The answer is “NO.”

Intervals are always in pairs. Every relationship between two notes can be defined by two intervals – up or down. Consider notes A and C. If C has a higher pitch, it is a minor 3rd above A, called an ascending interval. If interval note A has a higher pitch, then the interval is major 6th down from A, which is a descending interval.

Unless there is specific information about the two pitches, we always read the lower note as root and consider the guitar intervals clockwise. The convention is to use the “#” symbol if the interval is ascending and the “b” symbol if it is descending.

If you know the name of one of the intervals between two notes, you can easily find out the other one using the simple method below:

- Subtract the number associated with the interval names from 9.

- Interchange the major and minor quality. If the original interval is major, its inverted interval will be minor and vice-versa.

- Interchange the augmented and diminished intervals similarly.

- There is no change in the name of perfect intervals. Only we need to subtract the number from 9.

For example, if the original interval is minor 7th, it’s inverted and will be a major 2nd because (9-7) = 2, and minor interchanges with major.

Similarly, the inverted intervals of the perfect 5th and major 7th are the perfect 4th and minor 2nd, respectively. This is applicable to all the other intervals.

Chromatic and Diatonic Intervals

Another important concept in understanding intervals is the distinction between chromatic and diatonic intervals. The 12 notes and the set of intervals between them form a very large group known as the chromatic intervals.

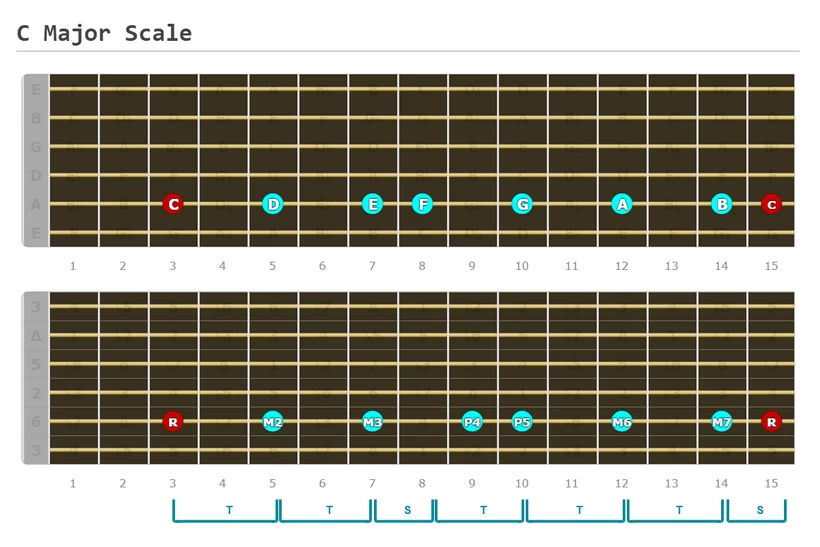

Diatonic intervals are a subset of the chromatic group and consist of only those intervals that the major scale is comprised of.

As you may be aware, the major scale is the most popular scale in music and is also a diatonic scale. Hence all intervals that make up the major scale are known as diatonic intervals.

The diatonic intervals are

- Perfect unison (C to C)

- Major second (C to D)

- Major third (C to E)

- Perfect fourth (C to F)

- Perfect fifth (C to G)

- Major sixth (C to A)

- Major seventh (C to B)

As mentioned earlier, diatonic intervals are subsets of chromatic intervals.

Interval Quality

Intervals can have five different qualities

- Major,

- Minor,

- Perfect,

- Augmented, and

- Diminished.

Major and minor intervals are commonly used in Western music, whereas perfect intervals have much more usage in ethnic music. We have discussed that the major and perfect intervals are the diatonic intervals. We get the minor interval if we reduce any major interval by one semitone.

Augmented and Diminished Intervals

Diminished and augmented guitar intervals are, in a way, hidden because they are only used in the internal structure of scales and chords that require them. These terms are necessary to abide by certain rules in music theory while writing out the notes and their intervals.

In our discussion on individual chromatic intervals, you would have noticed no major, minor or perfect designation for the interval with a distance of six semitones or three tones, commonly known as tritones.

Diminished intervals are one semitone below the minor and perfect intervals. As we have seen earlier, G is the perfect fifth for C. If we lower it by one semitone, we get “Gb,” a diminished fifth above C. We can get a diminished interval also by lowering a major interval by two semitones.

Similarly, raise or expand the perfect and major intervals by one semitone to get an augmented interval. You can also raise a minor interval by two semitones to get it. In our previous example, if we raise the perfect fourth “F” by one semitone, we get “F#” at an augmented fourth interval from C.

Augmented intervals are designated by capital A, while diminished intervals have a lowercase first letter.

The knowledge of intervals is essential because they are used to define the chords and scales. For example, if you know the natural minor scale, you can easily play the harmonic minor scale because the only difference between the change of minor 7th in the natural minor scale to major 7th in the harmonic minor scale. The same applies to melodic minor scales with raised 6th and 7th in ascending direction.

Conclusion

That’s all for intervals! In the next article, we will look at other topics about guitar music theory. I’ll see you then! Thanks for reading. Let me know in the comments section if there are any specific topics about intervals that you would like me to cover in more detail or if you require clarifications on the items covered.